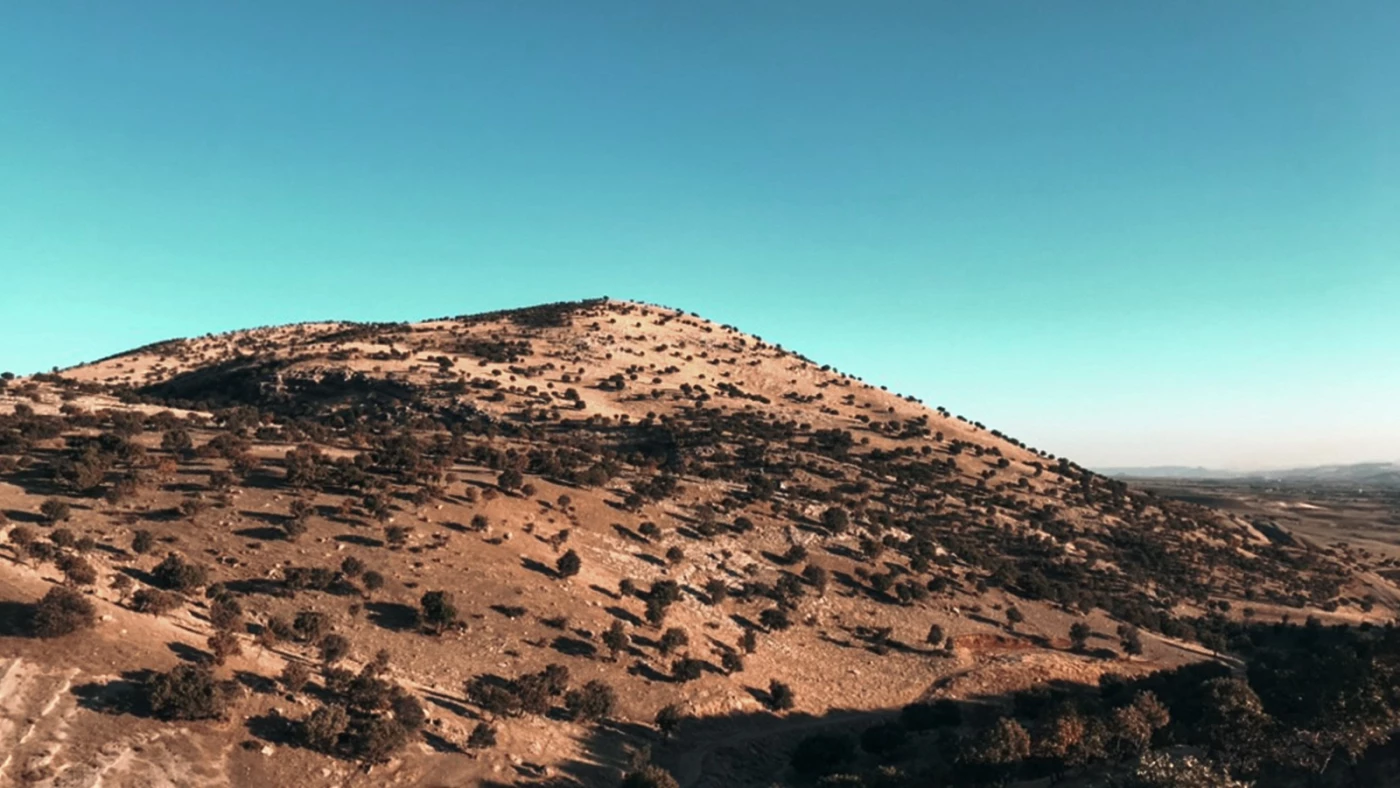

ERBIL, Kurdistan Region of Iraq - When traveling between cities in the Kurdistan Region you may notice old pine or eucalyptus trees alongside roads or close to city entrances. Near some urban centers, forests cover hillsides and mountain slopes. But how old are these trees, and who planted them? A survey published by the Region’s Ministry of Agriculture in 2015 provides the answer.

The report, titled Mapping and Estimating Vegetation Coverage in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region Using Remote Sensing and GIS, details how multiple satellites were used in 2014 and 2015 to survey the Region’s vegetation coverage, both natural and artificial.

“Traditional methods, including field surveys, are not effective for acquiring vegetation cover data due to their time-consuming and often costly nature, especially when covering large areas,” the report explains.

The department of forestry, officially called the Directorate of Horticulture, Forests and Rangeland, believes that such surveys are essential for the protection of green spaces and their future expansion, while they provide “valuable information for understanding natural and man-made environments by quantifying vegetation cover.“

The survey’s first phase, conducted in 2014, covered only Duhok province, and the second phase in 2015 covered Erbil, Sulaimani, and Garmiyan administration.

The mapping reveals significant variation in greenery across the Kurdistan Region: “The results showed that the ratio of vegetation coverage is about 12.44% of the total area of the Kurdistan Region, with 9.05% in Erbil, 9.1% in Sulaimani, 10.04% in Halabja, 4.4% in Garmian, and 27.58% in Duhok.”

Some of these figures do translate to reality on the ground. For example, Halabja and Duhok are often considered the greenest areas in the Kurdistan Region, and the MSN air quality map, one day of this past summer, showed Halabja as having comparatively the cleanest air among the Region’s four provinces.

The survey highlights that Amedi, a town standing out for its natural beauty in Duhok, has maximum vegetation coverage, while Bardarash in the same province has the least. Mergasur has the highest overall vegetation coverage, and Khanaqin the lowest.

In Kurdistan, there are two types of forests: natural and man-made. The natural forests mainly consist of oak trees in the remote, rugged mountains. Unfortunately, many of these forests have been cut down over the years, particularly during the economic hardships of the 1990s. Today, Kurdish parliamentary law No. 10 of 2012 offers some protection. Some natural areas have been destroyed by wildfires, while others are inaccessible due to landmines from the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s.

According to the survey, “The majority of natural forests are located in the Kurdistan Region and are estimated to account for 97% of Iraq’s natural forest areas.”

Man-made or artificial forests, including the tree clusters seen in and around cities, face challenges such as logging, fires, neglect, and land clearance for development. Yet, it is interesting to trace the history of these forests under different Iraqi and Kurdish governments.

For example, the cypress and pine forests near Shaqlawa were planted in 1977, some of the Zwita forests in Duhok date back to 1974, and the hills near Tasluja outside Sulaimani 1955. These were planted during earlier Iraqi governments, and many charts in the survey show that thousands of hectares of forests have been added since the creation of the autonomous Kurdistan Region in 1991. The survey counts trees in road medians and city parks as part of these man-made forests.

The 140-page study stresses that such a project should be repeated at least every ten years “to ensure comprehensive information on vegetation coverage and distribution, which will enable the Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources to implement effective management and planning programs.”

The last data available before this survey dated back to 1947 to 1949, gathered by British forest expert G.W. Chapman. In 1999, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) had conducted a survey under the Oil for Food Program, but the department notes that it “relied on old data” and did not consider “several climatic, environmental, and natural changes” over the past 60 to 70 years.

Satellite mapping being a time-efficient method for this survey, it still had faced certain challenges.

For example, mapping in Garmiyan was scheduled for June, but images were obtained at the end of July and August, when the “hot summer had already reduced vegetation coverage.” This delay may have led to underestimating vegetation in that area.

Other factors affecting the accuracy of the satellite imagery included land elevation. As explained in the report, “The estimated forest area will also be affected by the ground surface inclination (slope). The estimated forest area may increase as the ground surface tilts from a horizontal plane (planimetric) to a tilted plane.”

The department of forests lists the primary threats to both natural and man-made forests as the decline in rainfall due to climate change, rising temperatures, fires, and deforestation.

Facebook

Facebook

LinkedIn

LinkedIn

Telegram

Telegram

X

X