BAGHDAD, Iraq - Iraq’s plan to transfer prisoners from areas once occupied by the Islamic State (ISIS) to facilities closer to their home provinces has sparked controversy, with supporters calling it a humanitarian step and critics citing security and logistical concerns.

The National Security Advisory previously requested that the Ministry of Justice relocate inmates from provinces previously controlled by ISIS, including Anbar, Nineveh, Salahhaddin, and parts of Kirkuk and Diyala. The aim, officials said, is to facilitate family visitations and reduce the burden on prisoners' relatives.

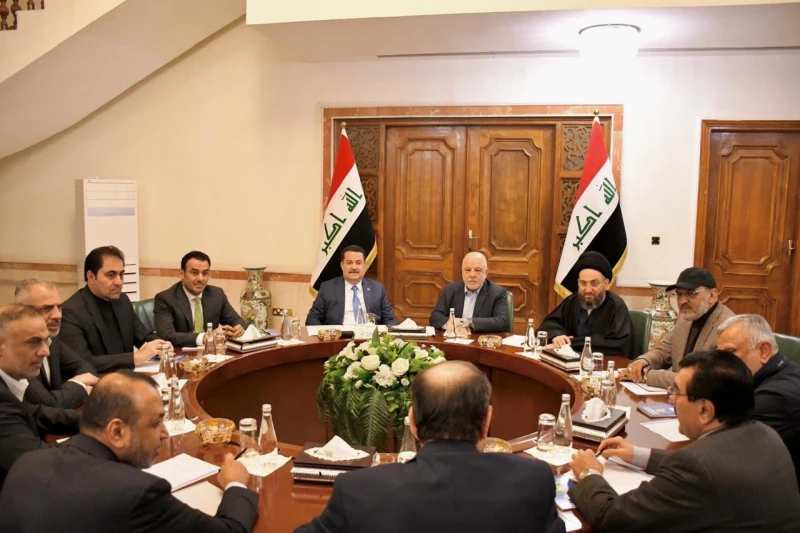

A document from the National Security Advisory outlined the directive issued by the Iraqi National Security Council during its January 22 session. The council called on the justice ministry to expedite prison rehabilitation efforts in Baghdad and other provinces, ensuring that inmates are distributed in accordance with Iraqi law and in consideration of humanitarian factors.

The decision has drawn pushback from the interior ministry’s rehabilitation and correction service. A directive issued by Major General Saleh Ali Abdul-Habib, head of the service, ordered prison directors to stop accepting new inmates and to halt prisoner transfers to courts and prosecutors.

The directive cited delayed budget allocations from the Ministry of Finance for December 2024, January, and February 2025. Abdul-Habib stated that Prime Minister Mohammed Shia' al-Sudani and the attorney general were working to resolve the issue, but ordered strict compliance with the suspension starting February 10. Violators, he warned, would be held accountable.

Lack of facilities in liberated areas

The justice ministry had already begun implementing prisoner relocations nearly two years before the National Security Advisory’s request, said ministry spokesperson Ahmed Laibi.

Laibi told The New Region that prisoners are categorized based on crime type and gender, with separate facilities for men and women and additional classification for terrorism, drug-related offenses, and human trafficking.

Most liberated provinces lack prison facilities, as post-war reconstruction efforts have focused on hospitals and schools rather than correctional institutions. The justice ministry, Laibi said, plans to open new correctional sections in Mosul and renovate Diyala Prison, but Salahaddin and Anbar remain without suitable facilities.

Security measures for transferred prisoners are being coordinated with the interior ministry, the National Security Advisory, and the National Intelligence Service.

Lawmakers call for action

Parliament member Mudhar al-Karawi said the issue of prisoner transfers is a top priority, given its humanitarian implications.

“Prime Minister Sudani approved the relocation of prisoners from liberated areas to nearby facilities to ease family visitations and facilitate the implementation of the General Amnesty Law,” Karawi told The New Region.

“The decision aims to reduce financial and logistical hardships for prisoners' families,” he added. Many families, he said, travel hundreds of kilometers to visit relatives in distant prisons, adding financial strain and legal complications.

Karawi also emphasized the need to reexamine cases involving secret informants to ensure justice.

Security and humanitarian considerations

Security and political analyst Ali al-Baydar called the decision an “administrative and humanitarian” measure, arguing that it meets longstanding demands from prisoners' families.

“It makes no sense for a Mosul resident to be imprisoned in Dhi Qar or for someone from Basra to be jailed in Baghdad,” Baydar said.

With Iraq’s security situation stabilized and updated security protocols in place, Baydar said the justice ministry’s involvement had turned the issue into a public debate.

He also noted that many prisoners could soon be released under amendments to the General Amnesty Law, which would ease overcrowding.

Prisons under pressure

Retired military advisor Majo General Safaa al-Asam said Iraq’s prisons are secure and well-protected, denying the security concerns over the proposed transfers.

“The transfer of prisoners to nearby facilities benefits both inmates and their families,” he said.

“Families often struggle to visit their relatives in faraway provinces, particularly when dealing with legal procedures through attorneys.”

Despite these assurances, Iraq’s prison system faces significant challenges.

A 2024 report by the Prison Justice Network described conditions in Iraqi prisons as “inhumane,” citing severe overcrowding, outdated facilities, and weak public prosecution oversight.

According to Shwan Saber, chairman of the network’s board, 80 percent of Iraqi prisons are unfit for human habitation. Many inmates convicted of minor offenses are housed alongside individuals convicted of murder and terrorism, worsening security risks and rehabilitation challenges.

The justice ministry estimates that Iraq’s prisons currently house about 60,000 inmates, three times their intended capacity of 20,000. Overcrowding, Saber said, has hindered rehabilitation programs and strained essential services, including healthcare.

As the government works to balance security, legal, and humanitarian concerns, prisoners and their families remain in limbo, awaiting clarity on whether Iraq’s latest reform effort will move forward, or stall due to financial and administrative hurdles.

Facebook

Facebook

LinkedIn

LinkedIn

Telegram

Telegram

X

X