BAGHDAD, Iraq - Nineteen years ago, Ithar Bahjat tried to stop her sister from traveling to Samarra. She pleaded and warned her, but Atwar was resolute. “I am headed to my city, do not be afraid,” she said, before she left home one last time.

She was in Kirkuk, and although another colleague was originally scheduled to go, Atwar insisted. It was as if she heard an inner calling that she simply could not ignore.

With confidence she said, “I am among my people and my city.”

Few hours later, she was recounting the story of Iraq for the last time, before she was assassinated.

On the night before her assassination, she was preparing to travel to Kirkuk. She planned to film an episode about oil wells for the program Special Mission, for Al Arabiya Channel.

Nothing seemed out of the ordinary except for a heavy feeling that this journey was different.

Ithar Bahjat recalled that Atwar’s behavior that day was unusual; she even refused to travel until after having her favorite meal, “biryani and decadent halawa,” and then she packed her bag.

When the car arrived, she suddenly turned; she stepped out and embraced her mother and her sister with a force she had never shown before. Looking at Ithar, she said, “I may not return.”

Her sister was shocked, “Say, 'Oh Allah,' go and then come back.”

Yet Atwar murmured something even stranger, “I feel that something will happen, the world will tremble for it.”

Explosion at the shrine; story cut short

The following morning, barely awake, Ithar was met with startling news: an explosion had occurred at the shrine of the two military Imams in Samarra.

It was an event that would change all of Iraq, and Atwar could not remain a bystander.

She set off for Samarra. Within just a few hours, Atwar Bahjat had vanished. She went straight there, dressed in pistachio green, determined to continue telling the story of Iraq.

Standing with the crew at the outskirts of the city, she was barred from entering due to widespread panic, and she delivered her report, her speech, and her final words.

“A message that the Iraqis seem most in need of remembering, whether Sunni or Shiite, Arab or Kurd, there is no difference between one Iraqi and another except for the fear for this country, from the outskirts of the Iraqi city of Samarra, Atwar Bahjat, Al Arabiya Channel.”

After that, the broadcast was cut off once and for all.

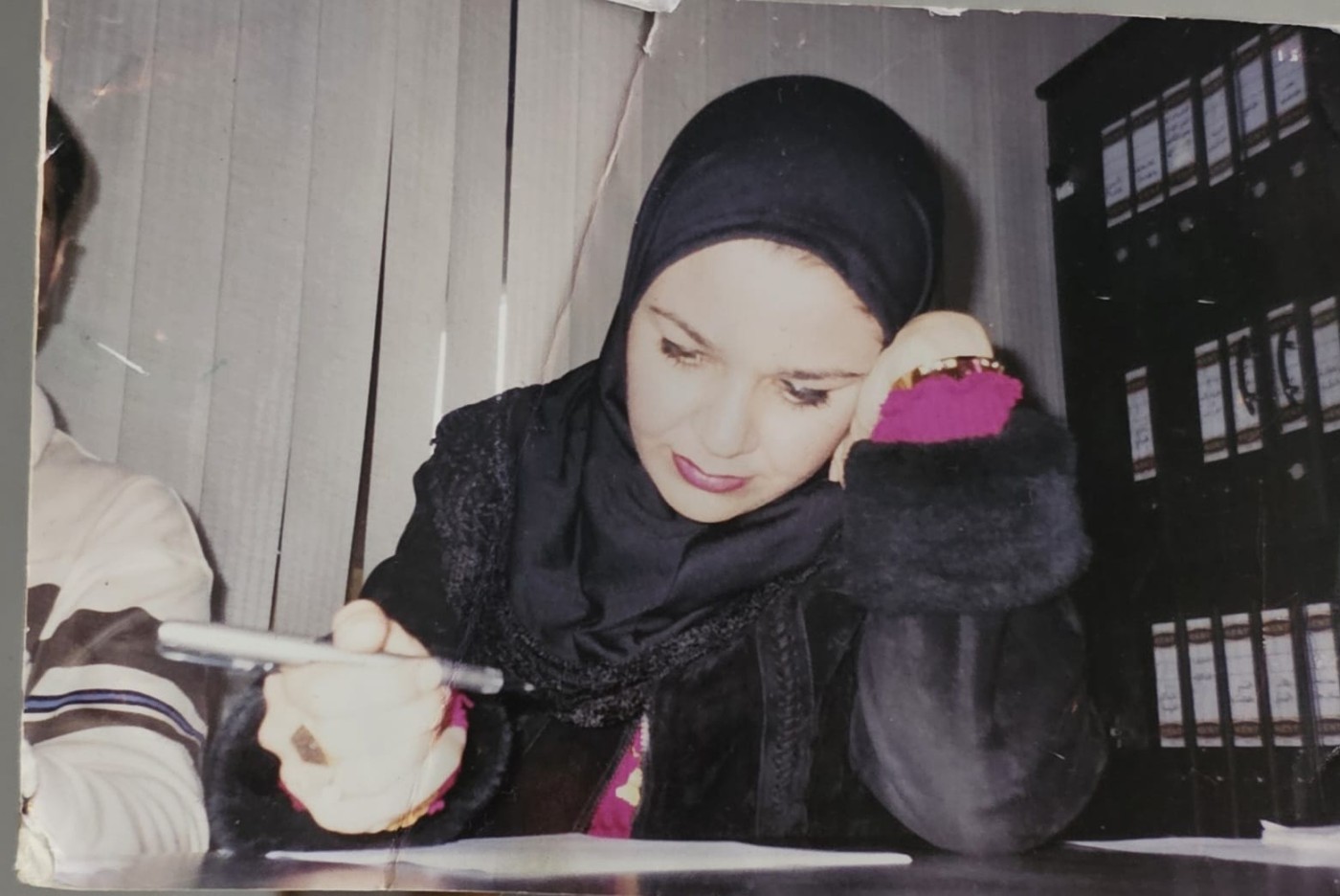

Atwar was born in Samarra, but she was far more than just a journalist; she studied Arabic at the College of Arts. She was a poet, a writer, and a voice that portrayed Iraq as no one had ever seen.

Before 2003, she worked with Iraqi news outlets, later moving to Al Jazeera and then Al Arabiya, yet she never once considered leaving Iraq despite all the threats.

Ithar explains that her sister received many offers to live abroad, but Atwar insisted that she would not travel but stay, and they refused.

The final direct threat she received came less than a year before her murder. She did not believe in fear, even though she witnessed war with her own eyes, and she did not believe in leaving, even when everyone told her it was the end.

Living on the edge of death

After the fall of the Saddam Hussein regime, she moved from one channel to another, eventually settling at Al Jazeera, only to leave for Al Arabiya just three weeks before her assassination.

She knew that every step along that path was fraught with danger, yet she never wavered. In the battles of Najaf, Atwar was covering the fighting when her colleague, journalist Rasheed Wali, was killed right before her eyes.

He was standing on a building’s roof when a sniper struck him with a bullet directly to the head.

No one could retrieve him amid the heavy gunfire. It was a scene capable of shattering anyone, it left Atwar unable to eat for three days, and kept saying that she still saw his image, drenched in blood.

That was not the only time the war brought her to the brink of death. While working at Al Jazeera, she was in a car with the channel’s crew when they drove on a landmine.

There was an explosion, chaos, and moments of panic, and somehow, they all survived, with her sustaining only injuries to her hand.

“Atwar lived death every day,” Ithar said.

Atwar became one of the most prominent martyrs of journalism, her name immortalized in a chronicle heavy with tragedies.

On the morning of Thursday, February 23, 2006, the world was informed of her assassination, just before she turned thirty, along with the crew who accompanied her, photographer Khalid Mahmoud al-Falahi, 39, and broadcast engineer Adnan Khair Allah, 36.

Their bodies were on their way to Baghdad, but roads in Samarra were closed down, so they did not arrive until five in the evening.

Immediate funerals were impossible, as the curfew was choking the capital, and the service was postponed until Friday after six in the evening, but even that was not enough.

As night fell, the curfew was reimposed at eight, making it impossible to reach and return from the Abu Ghraib cemetery. There was no choice but to keep Atwar Bahjat’s body at home for two consecutive days.

The difficult farewell

Ithar recounts that for more than six hours she was unable to reach Atwar’s phone number. She called the Al Arabiya office that knew what happened, but they could not tell her the truth.

“They later told me that she had been kidnapped; I went out barefoot, running and pleading with people in the street to help find my sister, who had been kidnapped in her own city,” she said. “The next day, they said she was dead. I spent hours unable to close my eyes, imagining what was happening to her at the hands of her captors, was she truly kidnapped, or had she been murdered from the start? I knew nothing, and no one answered me.”

Ithar did not want to see her sister’s lifeless corpse. However, those who saw her body said that Atwar was smiling, as if, despite death, she still clung to life.

The hours passed heavily, and after two days without a funeral due to the poor condition of the Iraqi roads, she had to be buried by any means.

The government refused to allow a burial amid the curfew until Al Arabiya intervened and contacted the Ministry of Interior, reminding them that “the honor of the dead is their burial.”

Finally, the family secured an exception, but at a cost: seven internal security vehicles were required to escort the body during the curfew. Initially, the family refused to put anyone, even members of the Interior at risk, as the situation was akin to street warfare, and they did not want to cause any commotion.

Many of her admirers could not come to bid farewell because of the curfew, but there was no other option.

The funeral procession set off as if the journey to the cemetery were part of the war. In one village, an altercation erupted. Explosive devices had been planted along the road; Interior forces came under gunfire, turning the procession into a target.

Three people were killed and others injured, yet Atwar’s body endured—as if she was being pushed toward death once again even after her martyrdom.

“Even in death, she was not granted a peaceful and calm farewell; even in death, the wars of Iraq continued to pursue her,” Ithar said, with a sorrow that still echoes in her voice after all these years.

The final chapter she never wrote

From her childhood, Atwar Bahjat was different. She did not indulge in frivolities like her peers, instead, she saved money to buy children’s magazines, read voraciously, and created for herself a world filled with words.

As she grew up, this was not merely a passing passion, it evolved into a life project, first expressed in a poetry group titled Violet Seductions. Later, she embarked on a novel entitled White Condolence, in which she recounted her experiences, her work, her fears, and her dreams, along with the pain she felt as she watched her country collapse before her eyes.

Yet she never finished it, for the final chapter of the novel ended with her murder, and the publishers decided to mark the work at the line that stated she had been killed.

She was steadfast in her convictions. She did not hide her unequivocal rejection of the American forces, she argued with them and refused reconciliation because of what they had done to Iraq.

Whenever she walked in her neighborhood and saw an American tank, she neither backed away nor showed fear, instead, she declared, “they are the ones who should be afraid.”

For her, work was not merely a professional ambition, but a responsibility. She was still a university student when she started working, she became the breadwinner, balancing journalism, studies, and writing, yet she never forgot her family.

She always made time to meet with her cousins, spend time with her mother and Ithar, and she allocated a portion of her income to help impoverished families on a monthly basis.

She knew that journalism might not grant her a long life, but she was determined that it would leave behind an unforgettable legacy.

Facebook

Facebook

LinkedIn

LinkedIn

Telegram

Telegram

X

X