In a rather unusual turn of events in Iraq, Shiite political elites have recently begun publicly floating the idea of establishing either a federal Shiite region or an independent Shiite state altogether.

The saga began in late February when, speaking of the broader regional changes in recent months, former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki told Dijla Channel that if Iraq were to break apart—something he claimed was part of an Israeli plot—the Shiites would no longer share resources with other communities in the country. “If some secede, the Shiites will not say ‘we will keep supporting you and offer you the oil.’ The Shiites will say ‘our oil will be for us as you will keep your resources for yourself.’ This is dangerous and we work for this not to happen,” he warned. He also alleged

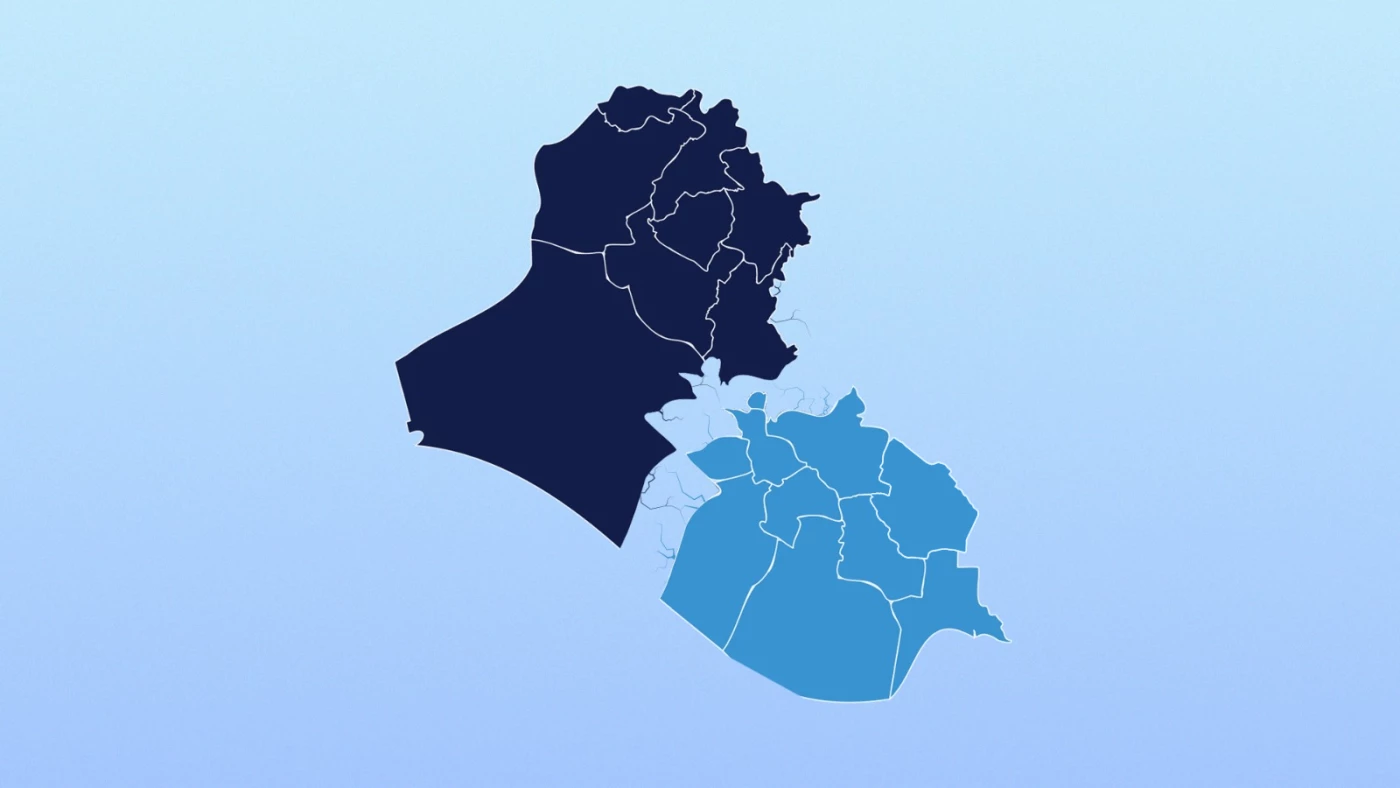

Shortly after, Hussein Muanis, a member of parliament from the pro-Iran Kataib Hezbollah group, told al-Ahad TV that if other factions refused to accept Shiite leadership in Iraq, then Shiite forces should either push for a federal Shiite region or consider “the option of independence of nine provinces.”

On March 24, Yusif al-Kilabi, another pro-Iran MP, reiterated the calls for a federal Shiite region or outright independence, adding that the resources of Shiite-majority provinces should not be allocated to other parts of the country.

This kind of talk is unprecedented in Iraqi politics—at least in recent memory—given both its nature and the stature of those articulating it. Given its growing frequency, it can no longer be dismissed as mere personal opinion.

It is significant for two reasons. First, it marks a major shift in tone among Shiite leaders. After nearly two decades of resisting autonomous regions in Shiite and Sunni Arab areas—despite Iraq’s federal constitution—this is the first time prominent Shiite figures have openly entertained the idea of establishing an autonomous region or even seceding from Iraq. Kurdistan remains the country’s only formal federal region. While Sunni groups and some Shiite activists have occasionally called for federal arrangements outside the Kurdistan Region, the Shiite-dominated establishment in Baghdad—including Maliki—has consistently opposed them. As recently as February 2024, Iraq’s judiciary chief, Faiq Zaidan, reaffirmed this stance, stating that “the idea of establishing another federal region was rejected because it threatened Iraq’s unity and security.”

Second, this sudden openness to federalism or even secession comes amid profound regional shifts following Hamas’s October 7 attacks on Israel, the war in Gaza, and the subsequent fallout. The deaths of senior Hezbollah commanders, the crippling of Hamas, and the fall of the Assad regime have all weakened the Iran-led axis in the region. In Iraq, this has emboldened Sunni forces who now sense an opportunity to push back against Shiite dominance.

Until mid-2024, Shiite factions exuded confidence in their hold over the Iraqi state. For more than a decade, the trend was toward recentralizing power in Baghdad—which effectively meant consolidating control in Shiite hands. That trend had reversed the early trajectory of post-Saddam Iraq, when Shiite parties like the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI) championed federalism as a safeguard against a return to an authoritarian system under a Sunni strongman. But by the late-2000s, most Shiite leaders had abandoned federalism.

Now, with key regional allies suffering blows and the United States and Israel conducting a relentless air campaign against the Houthis in Yemen, panic is setting in among Iraq’s Shiite political class. They fear Iraq could be next in line for destabilization. Central to their concerns is the belief that the US and Israel are orchestrating a regional restructuring to weaken or bring down Iran and its allies.

Though Iraq is not officially part of the Iran-led “axis of resistance,” Iran’s influence over Shiite political actors in Baghdad has been pivotal at key moments—during elections in 2010 and 2021, the war on the Islamic State (ISIS), and earlier in the fight against al-Qaeda in Iraq. Pro-Iran groups in Iraq often operate in a gray zone: while politically embedded in the state, their armed wings launch attacks on US and Israeli interests. In 2024 alone, they carried out some 200 such attacks.

The anxiety is further fueled by growing speculation in Iraqi media that the US wants the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) dismantled or restructured—specifically to exclude the Iran-aligned resistance factions. Iran’s Ambassador to Iraq Muhammad Kadhim Al Sadiq confirmed this in an interview with local media on March 27.

It is unclear whether these public statements about federalism and secession reflect an emerging plan B among Shiite elites—or if they are merely rhetorical tactics. Perhaps the goal is to scare Sunnis by warning them of the economic fallout of losing access to federal oil revenue, especially since Sunni areas have largely untapped natural resources. It could also be an effort to rally the Shiite base ahead of national elections expected later this year. Or perhaps it is all of the above.

Unsurprisingly, Sunni politicians have reacted. On March 17, Parliament Speaker Mahmoud al-Mashhadani advised Shiite leaders against floating the idea of autonomous regions. If the Shiites kept the oil, he said, then the Sunnis could keep the water from Tigris and Euphrates rivers. These waterways are vital for southern Iraq’s agriculture and daily life. Mashhadani later downplayed his remarks, saying they were taken out of context and did not reflect his political vision.

Former MP Mashan al-Jabouri weighed in on March 13, arguing that “good governance” was Iraq’s true solution—not partition, which he dismissed as “unrealistic”. He called for greater devolution of power from Baghdad to the provinces and supported the creation of administrative federal regions at the provincial level. In a March 26 post on X, he warned Shiite forces that they could not claim Baghdad if they opted for secession. He added that talk of dividing Iraq was “Iran’s last card,” asserting that Tehran has long seen Iraq as an “existential threat” and now seeks to divide it along sectarian lines.

Kurdish leaders, for their part, have remained quiet. Though Kurdish parties have historically supported the creation of other federal regions—as a way to dilute Baghdad’s dominance and balance power among Iraq’s ethnic and religious communities—the current rhetoric around federalism or secession has not prompted a noticeable response from them.

It is ironic, as former Najaf governor Adnan al-Zurfi—a Shiite politician—pointed out, that the very forces which long opposed federalism as an American plot to divide Iraq are now the ones raising the idea. However, what is clear in the statements by senior Shiite leaders, from Maliki to members of parliament, is a tacit acknowledgment that they have failed to govern inclusively. This underlying anxiety among the Shiite leaders about Iraq’s future stems from a growing realization that their domination of the state has alienated other communities.

There are, however, some signs that Shiite leaders may be trying to change course toward fairer governance. In a March 26 meeting between Maliki and Ammar al-Hakim, head of the National Wisdom Movement, the two leaders called for greater financial allocations and more authority for provincial governments.

Indeed, if Iraq adopts a more decentralized, equitable system that respects local communities’ rights to manage their own affairs, there is no reason Iraqis of all backgrounds cannot coexist peacefully in line with the country’s constitution. But unless this shift becomes more than just talk, the specter of division and partition—real or rhetorical—will continue to loom over Iraq’s fragile unity.

Facebook

Facebook

LinkedIn

LinkedIn

Telegram

Telegram

X

X