In the mid-fourth century BC, Alexander the Great embarked on his conquest of Asia, expanding his dominion across much of the known world. Selecting Babylon, located in present-day Iraq, as the seat of his vast empire, he strategically linked the ancient realms of the East and West.

Taking inspiration from Alexander's historic decision to establish Babylon as the heart of his empire, the Iraqi government has unveiled its own ambitious initiative dubbed the "Global Development Road”. This expansive project spans the length of the country, stretching from its southernmost shores along the Gulf to its northern border with Turkey, and even extending further into Europe.

Iraq sees this roadway as a crucial connection bridging the industrially vibrant nations of Asia with the technologically advanced, industrially robust, and agriculturally prosperous countries of Europe.

Stretching across 1200 kilometers, this corridor links the southern port of Faw to the Turkish border in the north via a network of railways and highways, passing through 10 Iraqi cities. The initial investment is estimated at $17 billion, with projected annual profits reaching approximately $5 billion.

Nevertheless, the complex tapestry of international politics presents three alternative pathways for global trade, all of which circumvent the Iraqi initiative. Complicating matters further are regional biases, internal hurdles including security risks, the sway of various factions, tribal dynamics, as well as financial challenges and the cautious stance of foreign investment firms. Moreover, without robust international involvement, the significance of the road diminishes.

This prompts the question: Can this Iraqi corridor effectively compete with alternative routes passing through Iran to Turkey or from Saudi Arabia to Israel? Will it truly have the potential to emerge as a global thoroughfare as envisioned?

Erdogan's visit and multilateral agreements

On April 22, 2024, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan made his first visit to Iraq in 13 years. The primary focus of the visit was the signing of a Strategic Framework Agreement for cooperation and a Memorandum of Understanding for the Development Road Project to advance the initiative.

Furthermore, security agreements were reached, which Turkey views as crucial to safeguarding the route and investing in it to realize its objectives of establishing a more direct pathway for global trade between the East and the West. This route would stretch from the Gulf shores through Iraq, Turkey, and terminate at European ports.

As part of the visit, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed for collaborative efforts between Iraq, Turkey, the UAE, and Qatar concerning the project. These nations declared their backing for the initiative and their preparedness to participate in it.

The memorandum entails the commitment of the signatory countries to establish the requisite frameworks for executing the project, which is anticipated to bolster international trade by offering a fresh, competitive transportation route, thereby fostering economic growth and bolstering regional and international cooperation.

The memorandum was signed by Iraqi Minister of Transport Razzaq Muhaibis, Turkish Minister of Transport and Infrastructure Abdul Qadir Oruç Oglu, Qatari Minister of Transport Jassim bin Saif al-Sulaiti, and Emirati Minister of Energy and Infrastructure Suhail Mohamed al-Mazrouei.

Iraqi officials stated that funding for the road will be sourced from a dedicated fund, with designated portions of oil shares earmarked for the project's imports. They highlighted that during Erdogan's visit, Iraq signed several memoranda of understanding encompassing economic, investment, and commercial aspects, facilitating greater cooperation in constructing the development road. These agreements, among the 24 signed memoranda, set the stage for enhanced collaboration.

In the Kurdistan Region, which operates under a federal governance structure, Kurdish officials voiced their aspiration for the Kurdistan Region to be included in the project during meetings with the Turkish President, who concluded his discussions there before returning to Turkey. Erdogan expressed his support for this sentiment and underscored the significance of the Region's involvement.

The actions taken by Iraq and Turkey, along with contributions from Gulf nations, underscore the importance of this road for the involved countries, with Iraq being particularly noteworthy. Iraq aims to initiate the project's first phase with the completion of the Faw Port by 2028 and intends to conclude it by 2050. These efforts come amidst global competition to establish novel international trade routes.

Russian, Chinese, and American corridors

In May 2023, Russia inked a deal with Iran to build a 162-kilometer railway linking the Iranian city of Rasht to the port of Sari on the Caspian Sea. This move aims to fill the gap in the North-South shipping corridor project, which stretches 7200 kilometers and connects Russia, Iran, and India. Russian Deputy Railway Director Sergei Pavlov confirmed this development.

The project's inaugural route stretches from Russia through Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, to the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas, culminating in India’s Mumbai. Another pathway comprises a maritime journey linking Russian ports on the northern Caspian Sea to Iranian ports on the southern shores. The third route spans from Russia's northern hub of St. Petersburg, traversing by rail to Azerbaijan in the south, ultimately reaching the Iranian city of Staraya. Upon the completion of the absent segment, it will further extend to the Iranian city of Rasht before advancing to India.

The Russian North-South Corridor

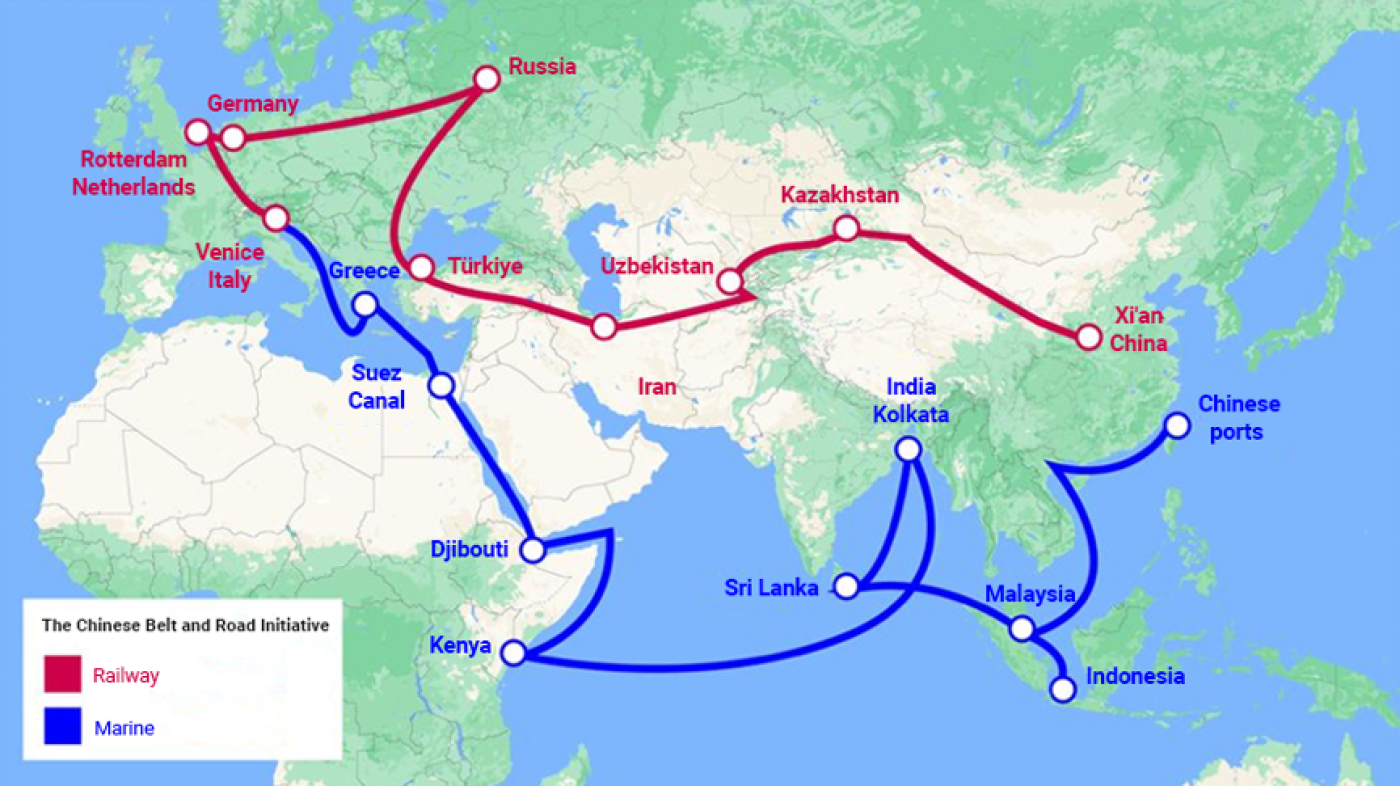

Meanwhile, China embarked on its grandest global venture, dubbed the Belt and Road Initiative, in 2013, aiming to rekindle the splendor of the historic Silk Road. Comprising both overland and maritime routes, it spans a colossal 10,000 kilometers, traversing 66 countries, with projected costs ranging from four to eight trillion dollars. The initiative encompasses the development of railways, oil pipelines, and power infrastructure.

The official blueprint of the overland route begins in the Chinese city of Xi'an, winds through Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Iran, eastern Turkey, and culminates in Istanbul. From there, it veers northward, stretching into Russia and Germany before reaching the port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands.

Regarding the maritime path, it spans from Chinese ports southward to Malaysia and Indonesia. From there, it heads north to Kolkata in India, then continues westward to Sri Lanka. Its journey proceeds to Kenya, Djibouti, and through the Suez Canal to Greece, concluding its voyage in Venice, Italy.

The Chinese Belt and Road Initiative

The spotlight intensified when China unveiled the Belt and Road Conference on September 7, 2023, with the goal of uniting 90 countries under its initiative. Yet, beyond the outlined routes by China and Russia, plans for additional corridors surfaced.

On September 9 of the same year, during the G20 summit in India, US President Joe Biden introduced what he dubbed the Great Passage project. This ambitious endeavor entails constructing railways and streamlining the movement of goods, renewable energy, and clean hydrogen through cables and pipelines between Asia and Europe, with an estimated investment of $3 trillion.

The American Economic Trade Passage project spans from Indian to Emirati ports through a maritime route. It then traverses railway tracks across Saudi Arabia to Jordan before reaching the Israeli port of Haifa. Subsequently, goods are transported by sea to the European Union.

The Iraqi government views the colossal projects of China, Russia, and the US as bypassing Iraq, thus missing out on promising economic opportunities. Despite this, Iraq welcomed the establishment of these projects, citing their economic significance for the region upon completion. However, it also emphasized that the proposed Iraqi Development Corridor stands as the shortest and most suitable route to the global market.

The Iraqi corridor slashes travel time from 33 days to a mere 15 and is set to transport 15 million passengers and 3.5 million containers in its initial phase. The second phase, projected for completion by 2038, is anticipated to handle 7.5 million containers and 33 million tons of goods. Transport Minister Razzaq al-Saadawi revealed plans for the third phase, scheduled for conclusion by 2050, aiming to accommodate 25 million containers.

Several Iraqi officials have underscored that while global roads, notably the American initiative, may remain as proposed concepts or encounter obstacles to realization akin to the challenges facing Chinese and Russian endeavors, progress on the Development Road is already underway, complete with a clear implementation timeline. Moreover, the Port of Faw is not just a vision but a tangible reality, with active construction underway, slated for completion by 2028, aligning with the initial phase of the Iraqi venture.

International Stances and Ramifications

Iraqi officials have noted a surge in the interest of various countries to partake in the Development Road project since its inception. This heightened enthusiasm, they assert, stems from the venture's pronounced investment appeal and strategic geographic positioning, particularly garnering attention from European nations.

The corridor promises substantial time and logistical efficiencies over traditional routes such as the Suez Canal, contingent upon a stable security environment—a prerequisite that underscores the imperative of political and social stability within Iraq.

Economic expert Nabil al-Marsumi highlighted a notable advantage of the road potentially extending to European territories or shores via Turkey. However, he also cautioned that the completion of this route could have adverse effects on the Suez Canal's traffic. Specifically, Marsumi suggested that the Iraqi road might impact the volume of transportation passing through the Egyptian canal, particularly for medium and small-sized goods. Nevertheless, he underscored that the Suez Canal will likely maintain its pivotal role in facilitating the transportation of large goods conducive to maritime conveyance.

Iraqi researchers emphasize the importance of safeguarding Iraq's interests, irrespective of the potential impact of its projects on other countries' interests. They assert that Iraq must prioritize its own strategic objectives and economic prosperity, regardless of the reactions or concerns of other nations.

Academic researcher Ayad al-Anbar emphasized that the decision to establish the Development Road is an Iraqi sovereign decision, describing the project as "a crucial investment objective for the country that must be pursued."

He suggested that countries like the United States of America are unlikely to oppose it but may seek to advance their interests through it, particularly as they lack involvement in other planned regional projects.

"Tehran shares a similar position and holds comparable ambitions and interests in seeing the project through,” he added. “It anticipates economic achievements through the accompanying investment momentum, alongside extensive and ongoing trade relations with Iraq."

Political factions' stances

Internal Iraqi positions regarding the Development Road project are generally aligned, with widespread support for its completion and calls to expedite the process. However, some Kurdish and Sunni Arab factions have voiced concerns or made observations regarding its routes and the entities tasked with executing and managing it.

Aqeel al-Fatlawi, a member of the State of Law Coalition within the Shiite Coordination Framework, emphasizes that the country urgently needs this "majestic artery" to diversify and enhance its economy.

"There is Iraqi political consensus on supporting the project due to its importance and necessity. It serves Iraq and other countries, as seen in their enthusiasm for its completion and their desire to participate," he added, expressing his conviction that it will inevitably come to fruition "due to the seriousness and political and parliamentary will show by everyone."

The Kurdish stance, in its general framework, expresses support for implementing the project, considering it as serving Iraq and the region. However, it raised some observations regarding its path not passing through some provinces of the region before reaching Turkey.

Officials in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) have held meetings with the authorities responsible for the project in the federal government to persuade them to route the main path of the road through Kurdish cities.

Harem Kamal Agha, an MP from the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), emphasized the Kurdish people's demand for their legal rights and share of strategic projects implemented in the country, questioning the economic benefits that will accrue to them.

The regional government is striving to secure an official agreement with the federal government regarding the extent of the road's coverage within the Region's borders, aiming to ensure benefits for the Region.

He emphasized that "the Kurdistan Region’s road represents the shortest and most advantageous route for the project," while also noting the presence of certain political parties—though unnamed—that appear to be aiming to withhold benefits from the region.

Sunni Arab forces have thrown their support behind the Faw-Turkey road, yet they have also raised reservations and inquiries.

Abdul Karim Abtan, an MP from the Sovereignty Alliance, emphasized Iraq's vital geographic and political position "as a hub for the four directions, and any route, whether by air or land, that bypasses Iraq will inevitably result in higher costs; this is a fact known to all nations worldwide."

The Sunni faction backs any road that benefits the populace and the nation's interests, "but Iraq will inevitably fall under the sway of whoever constructs this linkage, and the Sunnis will voice their concerns and viewpoints at that time," hinting at undisclosed stipulations that might subject Iraq to the influence of the project's architects and their collaborators, clarifying that "the execution process necessitates certain conditions, and debating them prematurely is premature."

Politicians representing the three main Iraqi factions are openly expressing their apprehensions regarding the project's completion. They cite several challenges, including the absence of conducive conditions to attract investments, security concerns in certain regions, the fragility of state institutions and legal frameworks, and the influence wielded by armed factions and tribes. These groups occasionally intervene to assert their own interests, posing a threat to project continuity. Similar disruptions have been witnessed in the operations of some oil companies in southern Iraq.

Implementation plan

The Iraqi government has yet to settle on the implementation mechanism for the project. Nonetheless, there are several suggested avenues for execution. One option is direct government funding, termed "contracting," which would demand a substantial amount of time due to its extensive financial needs.

Alternatively, there is the prospect of investment involvement, which becomes more feasible with an accord with international firms. Another avenue is collaborative operation and management with participating nations, or recourse to loans from global corporations.

Younis al-Kaabi, the Director-General of Railways, has shed light on some of the proposals put forth by the project's higher authority for its execution. A notable suggestion is investing in particular segments of the road.

Kaabi also highlighted several challenges faced by companies keen on undertaking the project. Some are hesitant to operate in select areas of Iraq due to security apprehensions and the tribal dynamics of those regions, which do not foster confidence in their endeavors.

Nonetheless, Kaabi noted that several global companies, including Chinese, Korean, and Turkish firms, have signaled their readiness to undertake the project. Furthermore, some European companies, alongside prominent local firms with a track record of executing diverse projects in Iraq, are keen on direct participation or partnerships with international entities for the development road.

Official sources have indicated that companies from Arab countries, primarily from the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Bahrain, have also expressed readiness to participate in the implementation. They aim to establish a presence in the industrial city projects and associated investments along both sides of the route.

Iraq has completed 50 percent of the initial designs for the project through an Italian company. The Turkish company conducted soil testing for a distance of 1,000 kilometers, while the remaining 200 kilometers, including minefields and a small section within the Kurdistan Region, are awaiting approvals, as confirmed by the Director-General of Railways. Additionally, he affirmed the participation of 18 Arab and foreign countries in the project.

Kaabi clarified that the railway included in the project would adhere to the European standard "Axle Load 25," which specifies the load capacity for two wheels. The anticipated speed for passenger trains is expected to reach 300 kilometers per hour, while for freight transport, it will be 140 kilometers per hour.

Iraq's aspirations for gas transportation

The Iraqi government has a proposal in its arsenal to extend a pipeline network parallel to the project's route for transporting natural gas from Iraq to Europe. This plan hinges on the completion of ongoing development works in the western and southern fields of the country. The initial stage is geared towards achieving self-sufficiency in gas within the next three to four years, paving the way for an export phase.

Qatar had previously inked agreements with both Shell and Total Energies, committing to supply each with up to 3.5 million tons annually of liquefied natural gas starting in 2026, for a span of 27 years. With plans to ramp up its liquefied natural gas production by over 60 percent to hit 126 million tons annually by 2027, Qatar is eyeing the potential establishment of a pipeline network extending across the Gulf waters. This network would stretch northward towards Iraq, then onward to Turkey and Europe, as suggested by international reports. Such a development could significantly slash the cost and time required for gas transportation compared to maritime transport over longer distances.

If realized, the Iraqi project could garner European backing, particularly as Europe hastens its search for alternatives to Russian gas.

Energy analysts highlight the feasibility of transporting Qatari gas either via LNG carriers in maritime routes or through an underwater pipeline network extending from Qatar to Umm Qasr port. The distance between the two points stands at a mere 650 kilometers, and there are firms prepared to undertake such ventures.

However, economists and researchers such as Suad Abdul Qadir, an expert in oil economics at Duhok University, cast doubt on Iraq's capability to attain gas self-sufficiency within five years. They argue that the current pace of work and attainment levels will not allow Iraq to begin gas exports for another eight to ten years. Consequently, Iraq will remain dependent on importing Iranian gas during this period.

"Transit" in Telecommunications and Internet Industry

Parliament member Aqeel al-Fatlawi has unveiled another promising development opportunity project named Transit, suggesting that Iraq could serve as a pivotal hub for connecting and transmitting fiber optic cables for telecommunications and the internet between Asia and Europe. The Ministry of Communications has inked memoranda of understanding with Saudi Arabia and other nations to explore this possibility.

This was corroborated by Younis al-Kaabi, the Director of Railways, who affirmed that the project encompasses a core cable running parallel to the routes of the Development Road by land. This initiative promises to bolster Iraq's communication networks and alleviate the intricate challenges linked with submarine cables.

Iraq grapples with chronic deficiencies in its internet infrastructure, compounded by issues with the cables sustaining it and elevated usage expenses relative to other nations.

During a televised interview, Minister of Communications Hayam al-Yasiri disclosed that one of the submarine cables originating from the port of Umm Qasr, managed by "Earth Link," has remained inactive, akin to a closed tap, since 2015.

She cited legal conflicts surrounding these cables upon assuming office, asserting that the company evaded responsibility for shuttering these access points.

Three scenarios for post-completion

Insights from experts in economics, transportation, and international trade outline three potential scenarios concerning the outlook and viability of the Development Road initiative, amidst the concurrent pursuit of three global trade route projects by China, Russia, and the United States.

The first scenario paints a picture of potential failure for the project on both international and regional fronts, stemming from its inability to meet the crucial criteria of stable governance, robust security measures, and a reliable legal framework.

According to economic expert Hamam al-Shammaa, while monopolizing global trade remains improbable, especially in the realm of transportation, theoretically, there is an opening to integrate the Iraqi project into global trade routes.

However, practical realities cast doubt on Iraq's capacity to ensure the security necessary for the globalization of this route. Shammaa noted that Iraq's current security landscape falls short of providing the requisite level of security, both internationally and regionally, for such a route.

Additionally, existing secure routes to Turkey offer viable alternatives, potentially confining the project's impact to a local scale. Shammaa poses a critical question: "Even if we manage to overcome the high costs, how do we address the security challenges and the presence of militias demanding tolls?" Consequently, the project may yield only localized benefits.

The second scenario envisions the project attaining success on a local and regional scale but falling short of becoming a global route in the face of the extensive projects and transport networks established by major global powers.

Economic expert Nabil al-Marsoumi proposed that upon completion, the Development Road project would undoubtedly benefit Iraq at a local level. However, given the existence of corridors orchestrated by Russia, China, and the United States, the Iraqi corridor is unlikely to attain international recognition and will likely remain a regional endeavor. Its scope may be confined to facilitating the transportation of basic goods between Turkey and the Gulf.

"The prospect of integrating global routes with the project post-completion remains viable, contingent upon Iraq's resolution of security challenges and internal disputes,” Marsoumi added.

This entails establishing a secure, administratively stable, and legally enforceable environment, instilling confidence in foreign investors to engage in the transportation of goods and passengers along the route.

In the present Iraqi context, economic expert Nabil Jabbar anticipates that the government will inevitably opt for a contracting system to execute the project.

Requiring $3.5 billion to finalize the initial phase, implementation faces delays, reminiscent of Umm Qasr port's 13-year construction duration, attributed to the dearth of foreign investors. Ultimately, the government collaborated with the Korean firm Daewoo through a contracting system.

"Given the existing conditions, foreign investment firms are unlikely to allocate a single dinar to Iraq's Development Road,” Jabbar said.

The third scenario entails the project's triumph as a global trade route, presenting the most optimistic outlook yet the least probable to materialize.

Jabbar suggested that the architects of the Development Road aspire to integrate the route into a segment of the expanding global trade transport activities, capitalizing on the escalating international demand for energy transit between the Gulf and Europe. This prospect could catalyze and elevate the project, particularly concerning gas conveyance.

There is speculation that the project could be integrated into global transportation routes, contingent upon several factors. Chief among these are the uninterrupted flow of transportation regardless of circumstances, lowered insurance costs and transit fees, and the establishment of free trade and industrial zones. However, paramount among these considerations is ensuring security along the road.

Official Iraqi sources are highly optimistic about the project, buoyed by promising indicators such as substantial initial offers from various countries, including commitments to financing and investment. Moreover, there is keen interest from several nations in participating. Turkey, for instance, is eyeing market expansion into Arab countries, while Saudi Arabia is keen on broadening its non-oil export base.

The overall landscape presents a promising trajectory for the Iraqi road, poised to transcend local and regional boundaries to attain global significance, thanks to its strategic geographical position bridging Asia and Europe.

Yet, it is a route fraught with potential hurdles that could impede its progress, among them, the prospect of involving the Kurdistan Region in the project, offering shares and benefits to garner support for the road's passage through Kurdish territories to Turkey.

Furthermore, the impediments of swift shifts in government administration, occasionally resulting in policy alterations, along with the security challenges posed by militias and their actions beyond the state's jurisdiction to enforce their demands, technical shortcomings in securing the route from south to north, as well as the tribal dynamics and unregulated arms proliferation that elude state control through legal means, all serve as barriers to instilling confidence in foreign companies to engage and invest in the project.

Should these obstacles persist without substantive remedies, they will not just impede the realization of the Development Road project and its evolution into a regional or global commercial corridor; they could render it susceptible to corruption and confine it to a mere local initiative unable to even recoup its construction expenses.

* This feature was produced in collaboration with the Network of Iraqi Reporters for Investigative Journalism (NIRIJ)

Facebook

Facebook

LinkedIn

LinkedIn

Telegram

Telegram

X

X