Mohammed Ali, a 65-year-old retired high school teacher, embarked on a significant life change at the start of 2022. He sold his home in Baghdad's bustling Media District and used the proceeds to purchase two houses in Sulaymaniyah. Seeking a quieter lifestyle, Mohammed and his wife settled into one of the houses, while putting the other up for rent.

Reflecting on his relocation to Sulaymaniyah, Mohammed Ali explains, "Living in Baghdad was a constant struggle with electricity and water shortages, not to mention the relentless traffic congestion that takes a toll on one's mental health. The recurring issue of sewage backups, caused by deteriorating pipes, resulted in our neighborhood flooding during the rainy season, with water getting into our homes in winter. The scorching summer heat only added to the discomfort. That's why I had already begun planning my move long before my retirement."

His three children and their families, based in Baghdad, eagerly spend their spring and summer breaks at his Sulaymaniyah residence. Mohammed Ali reveals that they all express a desire to relocate permanently to be near him, yet they remain tied to their positions in government and private jobs.

Iraqi citizens relocating to the Kurdistan Region is not a recent phenomenon. Following the downfall of the Saddam regime in 2003, hundreds of thousands, like Mohammed Ali, made the decision to move, drawn by the promise of security and the availability of public services in the region. Integrating into the community, they've played a significant role in its economic growth and cultural enrichment. Some have learned the Kurdish language to better assimilate.

The KRI is home to approximately one million Iraqi citizens of Arab descent, according to official statistics. This population includes individuals who sought refuge in the region to escape violence, particularly following the rise of ISIS in parts of Iraq in 2014. Others have migrated over the past two decades for employment and trade opportunities.

The decision by the regional government in 2018 to permit non-Kurds to own properties in Kurdistan, including land and residential houses, without the need for special security approvals, has led to a notable rise in the number of individuals seeking permanent residency.

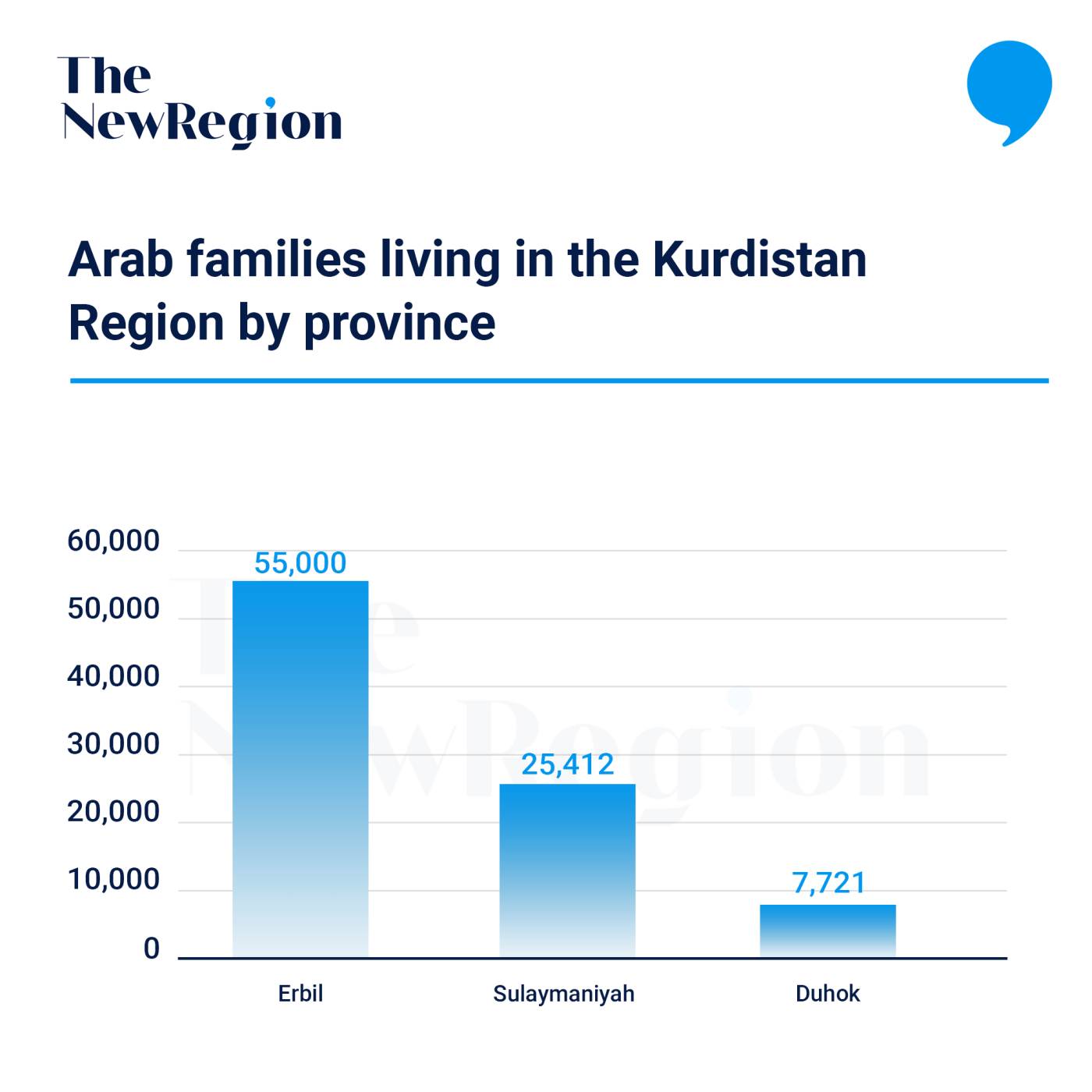

According to statistics published in 2022, there are approximately 55,000 Arab families residing in Erbil Governorate, 25,412 families in Sulaymaniyah, and 7,721 families in Duhok Governorate. Meanwhile, the regional government estimates that around 665,000 internally displaced persons have been living in camps established for them in the region since 2014.

Social researcher Hiwa Omar attributes the expansion of the Arab presence in Erbil to its status as the region's capital, offering more job opportunities compared to other provinces, along with its developed infrastructure. "Erbil is also geographically closest to three provinces—Nineveh, Salahuddin, and Kirkuk—that were heavily affected by the ISIS invasion. Consequently, it has become a preferred destination for displaced individuals from these provinces seeking refuge and settlement."

Arab Iraqis seeking residency in the region must undertake legal procedures to obtain a three-month residency permit, which can then be renewed. To qualify for an extension to a one-year residency, they must demonstrate their residency in the region through a lease agreement or proof of residential property ownership. Kurds relocating from other provinces are exempt from these requirements.

However, according to lawyer Nada Ibrahim, this residency may be revoked under certain circumstances, such as if the resident is found to be engaged in terrorist activities or has committed a crime, or if a lawsuit has been filed against them resulting in imprisonment.

Arab residents in the region are given the vote and a right to stand in elections, on the condition that their social security cards are issued from one of the region's provinces. They also have the option to transfer their social security cards to the region, although local officials indicate that the process is complex.

The social security, or “ration” card, is a staple possession for every Iraqi family. They were issued during the 1990s in response to the economic sanctions imposed on Iraq by the United Nations following the invasion of Kuwait. As a means of supporting families amidst hardships, the state provided essential rationed goods. Over time, the card has evolved into a vital document required for various official transactions.

Real estate takeover

Mohammed, a 40-year-old Ministry of Health employee, found himself grappling with the skyrocketing real estate prices in Baghdad following his marriage. As he describes it, owning "an inch of land" became an unattainable dream. The burden of the $500 monthly rent for his house intensified, particularly after welcoming twins into his family.

He explains, "With my wife unable to work after the birth of our children, and my salary barely covering our expenses, I knew something had to change. Realizing that real estate prices in Erbil were significantly lower than those in Baghdad, coupled with better services and a more stable security situation, I made the decision in 2022 to invest in an apartment and relocate here."

Mohammed successfully arranged an initial payment of $20,000 and bought an apartment in the Lalav City Complex, located on the outskirts of Erbil. Despite his transfer to the Health Department in Kirkuk, situated 96 km south of Erbil, Mohammed doesn't see any inconvenience in commuting daily, a journey that takes about an hour each way.

Speaking about the residential complex in which he lives, Mohammed notes, "The monthly installment for my apartment is $400, which is lower than the rent I used to pay in Baghdad. Commuting to work is better compared to Baghdad, where congestion required me to leave two hours before my shift started. Here, I own the apartment I live in."

Smiling, he adds, "Everything has improved. If I hadn't decided to move to Erbil, I might have resorted to informal settlements to escape high rent, and I would have continued to struggle with deteriorating services, chaos, and fears of eviction."

By "informal settlements," he refers to houses constructed on state-owned land on the outskirts of the federal capital, Baghdad. These properties come at low prices, but basic services are lacking. Buyers hold onto the hope that the state will eventually grant them ownership. However, residents live with the threat of eviction at any time.

Advertisements for real estate installment sales proliferate across the provinces of the Kurdistan Region on social media. Many of these ads are geared towards Arabs, published in Arabic. The prices advertised are attractive, often less than half or even a third of what similar properties would cost in Baghdad.

Dana Omar, a real estate marketer, asserts that Arabs have "undoubtedly become an integral part of the community in the region." He highlights that some high rise residential complexes are primarily occupied by Arabs. This demographic includes retirees and employees who have the flexibility to relocate their jobs to Kirkuk, Mosul, or even other provinces further afield.

He elaborates, "The inclination of Arabs towards acquiring real estate through installment plans extends beyond modern complexes. Many also opt to purchase houses in conventional residential neighborhoods, where prices typically fall below those in the complexes. This option is favorable for individuals who have sold their homes, perhaps in Baghdad or Mosul, and seek to invest while retaining some capital. Generally, properties in Kurdistan offer more affordability and superior amenities."

Real estate sales and rental agencies in Erbil and Sulaymaniyah have a significant reliance on Arab clientele, comprising as much as 60% of their customer base. These individuals seek stability in the Kurdistan Region and come from a diverse spectrum of professions and backgrounds. Among them are traders, investors, medical practitioners, university faculty, retirees, employees of non-governmental organizations or international bodies, as well as workers in specialized fields.

Dana states that property prices in the Kurdistan Region fluctuate based on factors such as location and property size. He notes, "With $40,000, one can purchase a basic property, while the down payment for apartments in residential complexes typically doesn't surpass $20,000. Moreover, there's a structured installment plan spread over several years, offering something not commonly found in other regions of the country."

Arabic-language schools are well established in the Kurdistan Region, initially under the KRG Ministry of Education, predating the conflict of 2014. Following the displacement of hundreds of thousands due to ISIS control over Iraqi provinces, additional schools were opened under the representation of the Ministry of Education in the federal government in Baghdad. Additionally, private schools and centers teaching Arabic have emerged, catering to Kurdish citizens.

Rising costs

Economic experts contend that recent economic turmoil in the Kurdistan Region, stemming from disputes between the regional and federal governments over oil exports and border crossing revenues, has impacted the purchasing power of Kurdish citizens. The depreciation of the Iraqi dinar against the dollar has compounded this issue, fostering an uptick in Arab presence in Kurdistan.

Kurdish economist Alan Momtaz sheds light on the correlation between the Arab influx in the Kurdistan Region and the surge in prices. "Undoubtedly, the heightened demand for real estate has driven up prices when measured in dinars. Nonetheless, the funds expended by the majority of Arabs originate from outside the region and wield an economic multiplier effect," he says.

Momtaz connects the decrease in the buying power of Kurdish residents to issues with Baghdad and complications in economic policy. "Persistent mismanagement of regional resources and the economic standoff between regional authorities and the federal government, which utilizes employee salaries as leverage, have disrupted the timely disbursement of salaries in the region. This has had adverse effects across various sectors and resulted in an economic downturn in the region."

As salary payments stagnated and an economic downturn gripped Kurdistan, a gap emerged between the purchasing power of Kurdish locals and the incomes of Arab migrants, who consistently earned money from sources outside the region.

Momtaz criticizes what he characterizes as efforts by certain parties to stoke tensions between different ethnic groups and persuade Kurdish residents in the region to oppose the policy of welcoming Arab migrants, claiming they drive up prices. "This assertion is unfounded, as the presence of Arabs in the region yields numerous economic advantages."

He contends that the escalation in prices within the region stems from monopolistic pressures imposed by market forces, rather than from incoming Arab consumers. This situation, he claims, leads to "an inequity in the positive economic multiplier effect across social strata. Market monopolists in the region place strain on the incomes of lower socioeconomic classes and appropriate the majority of economic gains."

Momtaz underscores that the Kurdish citizen, perceiving the inflationary repercussions of Arab migrants' expenditure as outweighing the benefits of the economic multiplier, is not a casualty of the incoming Arab migrants but rather of the market monopolists.

Kamaran Ahmed, an economics professor at the University of Sulaymaniyah, highlights another aspect influenced by the growing stability of Arabs in the Kurdistan Region: the competition for existing job opportunities, particularly as they are willing to accept lower wages. He explains, "Arab workers are accepting lower wages compared to Kurdish workers, leading to higher unemployment rates among Kurdish laborers. Nevertheless, it has also facilitated the provision of services at reduced and more competitive prices."

In response, the regional government has instructed investors across all sectors to ensure that 75% of their workforce comprises Kurds. Nevertheless, numerous companies and business owners fail to adhere to these directives and employ various tactics to bypass them in order to maximize their profits.

Kamaran explains, "Basic private sector enterprises like construction, cleaning services, as well as the restaurant and market sales sectors, experience heightened competition between Arabs and Kurds compared to other sectors, primarily because of the surplus of Arab labor following the waves of displacement in 2014."

Disruption and reconnection

Geographically, Arabs and Kurds in Iraq have a history of intertwined relations and numerous cultural and economic connections. Bakhshan Zankana, a former deputy in the Kurdistan Parliament tells The New Region, "During many political turning points, there existed a strong sense of solidarity between the two ethnic groups. Despite the discriminatory policies of past Iraqi regimes against the Kurds, which at times escalated to ethnic cleansing, such as the scorched-earth tactics of the chemical bombings and Anfal operations of the 1980s, there was a general atmosphere of camaraderie between them."

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq, in its present boundaries, was formed in 1991 under international safeguard and the supervision of the United Nations, following the Kurdish uprising against the Ba'athist regime. Subsequently, the rapport between the inhabitants of the region and the Arabs in other areas of Iraq experienced a two decade hiatus, during which they remained relatively estranged until the downfall of Saddam Hussein's regime in 2003.

Zankana sheds light on facets of that era, remarking, "There existed a sort of economic, social, and cultural autonomy and detachment between the majority of Kurdistan and other areas of Iraq. A Kurdish generation arose that eschewed the Arabic language, with its familiarity and perceptions of the remainder of Iraq being scant and largely unfavorable owing to the protracted rule of the Ba'ath Party. Moreover, Kurdish national sentiment was bolstered."

Circumstances shifted after 2003, fostering a rapprochement between the communities. Kurds played a role in molding the nascent state, crafting its constitution, and safeguarding its institutions via the Peshmerga forces. These forces were deployed in Baghdad, Nineveh, and Kirkuk, securing critical areas during the sectarian strife and the proliferation of terrorist organizations.

40 year-old Um Hussein relocated from Baghdad to Sulaymaniyah with her husband and children in the wake of sectarian violence in 2006. "Death loomed around us," she recalls, "and our only option was to flee to the Kurdistan Region to ensure our survival."

Thousands of families, including those of high-ranking government officials, fled the sectarian violence that erupted between Sunni and Shiite Arabs from 2004 to 2008. They sought refuge in the comparative security of Kurdistan, where the risk of being targeted by armed groups was significantly reduced.

Um Hussein adds, "And now, after all these years, it was the best decision we made. There is no room for sectarian and nationalist tensions here. We live in complete safety and away from many events that may have endangered our lives."

Even with security returning to parts of Iraq, Um Hussein remains steadfast in her decision not to return: "I will not go back. My family and I have become part of this community. My husband owns a clothing store, and my children are in university studying engineering and programming. They grew up with their Kurdish peers and speak Kurdish fluently."

Opposition and support

The continuing influx of Arabs into the Kurdistan region raises concerns for some Kurds, such as 20 year old Makuwan Mohammed, selling fruit and vegetables near the Qalat Market in Erbil. He voices his apprehension about the region potentially transforming into an Arab-dominated area. "As Arabs increasingly populate the markets and residential areas, Kurdistan risks losing its identity. While it's true that tourism depends significantly on them, their migration to settle here has increased economic challenges for us. They are now vying with us for the limited job opportunities available."

He gestures towards the shops, saying in colloquial Arabic, "Practically every shop here is run by Arabs. They're competing with locals for employment, and we've all had to pick up Arabic because many customers are Arabs."

In response to market demands, individuals like Makuwan have found themselves compelled to acquire proficiency in Arabic, a language they had no prior familiarity with years ago. Furthermore, a significant number of establishments including shops, companies, restaurants, hospitals, and medical clinics employ signage in Arabic.

In contrast to Makuwan's perspective, Sherko Mustafa, a 50 year-old employed at Qalat Market, views the influx of Arabic speakers as a chance to foster renewed dialogue between Kurds and Arabs. He perceives this as a means to "overcome the prevailing prejudices among Kurdish youth stemming from past nationalist policies."

Former Deputy Bakhshan claims that not all is rosy, asserting, "the chauvinistic acts of appropriating Kurdish lands in regions designated as disputed territories by the constitution, coupled with discriminatory practices against Kurdish inhabitants, have cultivated animosity between the two factions at a grassroots level in certain areas, notably in Kirkuk."

Salah Ali, a Kurdish lawyer representing numerous Arab clients, underscores this point, stating, "These policies need to cease, with concerted efforts directed towards fostering harmonious coexistence among the diverse constituents within all Iraqi cities. It's imperative to address the underlying issues that ignite sensitivities."

Certain Kurdish citizens harbor apprehensions regarding the growing Arab population in the Kurdistan Region, compounded by lingering unresolved disputes between respective governments. Nevertheless, these concerns do not alter the overarching atmosphere within Kurdish society, characterized by an ethos of openness and hospitality towards many Iraqi Arabs who opt for the Kurdistan Region as a haven for stability in their lives. This decision underscores their sense of reassurance, comfort, and contentment.

Civil activist Hussein al-Janabi outlines several cultural and social factors driving Arabs' preference for the region and their decision to establish roots there. He explains, "The prevailing civil ethos fosters a sense of security, with a robust legal framework and ample room for personal freedoms. Additionally, the absence of armed militias enhances the region's appeal, making it a sanctuary for numerous activists, journalists, and politicians seeking safety and stability."

Al-Janabi reflects on the October 2019 protests that swept through central and southern Iraq, driven by grievances against corruption and the ineptitude of the ruling class. "Protesters encountered violence, with activists becoming targets of armed factions. Seeking refuge, many fled with their families to the provinces within the Kurdistan Region to safeguard their lives."

* This feature was produced in collaboration with the Network of Iraqi Reporters for Investigative Journalism (NIRIJ)

Facebook

Facebook

LinkedIn

LinkedIn

Telegram

Telegram

X

X