BAGHDAD, Iraq - Mohammad Waleed, 31, was forced to make fundamental changes in the family home located in the al-Atifiyah neighborhood in the center of the Iraqi capital, Baghdad. He is the eldest of three brothers who inherited the house from their father and had to divide it so each of them could benefit and live next to each other rather than selling it and sharing the money, as sharing the money would not be enough for either of them to buy a new house.

Baghdad, home to around 8 million people, is among the most expensive cities in terms of real estate prices. In certain areas of Baghdad, a 300 square meter plot of land could cost hundreds of millions of dollars and apartment rental on average exceeds 500 dollars, which is equivalent to the salary of an average civil servant.

“This was one of the only times I invested in my studies,” Waleed said, pointing to his bachelor’s degree in civil engineering hanging on the wall above his head. “I work in a cosmetics store with a limited monthly salary, it is an unstable job which I cannot rent a house with, and the same is true for my two brothers who work as freelancers.”

“We did not get employed by the government, making it difficult for us to obtain loans and build our own houses, because we are not government employees, journalists, or party members, there are no residential lands distributed to us,” he added, laughing loudly and moving his hand like a knife.

“So I cut the house into three parts, and each of us lives in one part with their family now.”

Waleed’s solution is the same thousands of Iraqis have resorted to in Baghdad, dividing houses built on an area anywhere between 250 to 500 square meters to include more than one house and several floors.

Some even have to resort to dividing buildings with an area of less than 200 meters.

Due to rising real estate prices, rental fees, and the scarcity of residential land, the number of buildings in Baghdad has multiplied dramatically at the expense of open spaces and gardens that have disappeared, leading some to refer to Baghdad as the “Concrete City”.

The last time there was a census for buildings in Baghdad was in 2009. At the time, the census showed that there were about two million buildings in Baghdad, this includes residential, commercial, and governmental buildings.

Real estate specialists believe that the number has doubled in the past fourteen years due to the momentum of movement from the southern governorates and the areas surrounding the capital to the center of the city to search for job opportunities.

The displacement of many others from areas that were controlled by the Islamic State (ISIS) in 2014 to Baghdad, is also another reason that experts anticipate that the amount of buildings in Baghdad has doubled.

Real estate office owners, engineers, and investors believe that the housing crisis has led many property owners to invest in their properties to the maximum extent possible, by cutting their buildings up and selling them, or by creating additional buildings on them that required major design changes, as a result, distorting the features of entire neighborhoods and destroying the traditional Baghdad buildings with gardens and turning them into heterogeneous buildings rising several stories.

Dozens of residential complexes have been built in the city in recent years, on lands that include neglected civil facilities, green spaces, or unused lands belonging to specific state institutions.

This has been done to keep at pace with the rapid population growth, which according to estimates from the Ministry of Planning, is approaching a two million increase in population between 2009 and 2020.

Additionally, large numbers of shopping complexes (malls) and multi-story commercial buildings have been built in the Iraqi capital.

“This has changed the urban face of Baghdad and distorted its basic design,” Adel al-Ardawi, historian and researcher in Baghdadi heritage, said. “A severe housing crisis and a significant increase in population led to the division of large houses into smaller ones and the increase of random housing in random locations.”

He believed that in order to preserve what is left of Baghdad’s urban design, decisions from a place of power are required, and that place of power is not on the municipality or even at the Ministry of Construction and Housing level.

According to Ardawi, there needs to be a decision “eliminating slums, distributing plots of lands to citizens, and facilitating loans to build houses.”

Slums and lands sold illegally

On December 2021, the ministry of planning announced that baghdad is ranked first in the number of slums (housing built without official approvals of state-owned lands, some of which are agricultural) with 522 thousand units, an increase of three times what these informal settlements were in 2017, as its numbers at the time was around 137 thousand, according to the national platform for reconstruction and development.

Mohammed Issam is a 46 year old government employee who lives in the Zayouna area and has worked as a land surveyor for years.

“The presence of half a million random homes in which over two million people live shows the extent of the urban distortion taking place and the depth of the services disaster in Baghdad,” Issam said. “Those people need roads, sewers, hospitals, schools, water, and electricity,” he added.

Like many others, Issam lives in a neighborhood that was once filled with houses with large gardens, but now, it is filled with concrete blocks and split up houses.

According to Issam, it is either cutting up your house or living in the slums.

A real estate office owner in Baghdad’s most populated area, Sadr City, said that the slums are most commonly built on agricultural lands that have been divided by its owners into plots not larger than 200 square meters and sold to people without any legal contract or ownership.

According to him, the property is registered as agricultural and is not permissible to separate it.

The price of these lands range between 10 to 20 thousand dollars, which is extremely low compared to lands that are legally owned.

“That is why people with limited income resort to buying agricultural land and constructing low-cost houses on them, with the hope that they will be registered some day,” he said, adding that this has led to thousands of such constructions without any control.

Those living on the agricultural lands have copies of contracts, known as Deed 25, which is a deed for agricultural lands owned by more than one person.

Whenever someone sells the land, their name is replaced with that of the buyer. They could also separate the land from the others while keeping it agricultural but that process is very expensive.

Al-Saddah area is one of the places with the most slums built. Before 2003, the area bordered Sadr city.

Today, it includes residential neighborhoods with the majority of it being simple inexpensive housing, and the price of plots of land there do not exceed 10 thousand dollars.

Because the area is not registered and the relevant authorities have not granted it necessary approvals, there is no legal access to water or electricity, leading owners to bypass public networks and get away with not paying for it.

Hussein Mohammed, 40, bought a plot of 100 square meter land around five years ago in al-Saddah area for 6000 dollars.

To build a house on it, he was forced to sell his taxi, sacrificing the means that provided him, his wife, and four children with daily food. He currently works as a porter in the Shorja market in central Baghdad.

“I had to do this, because rent is very burdensome and even if the state refuses to give me ownership of the house after years, and I decide to demolish it, the loss will not be too much because I used cheap thermstone material instead of bricks in construction, as well as used doors and windows,” he said.

“It will be much less than if I had paid rent during my years of occupying a house elsewhere,” he added, “but if the state gives me ownership of the house, as it has happened with many others in Baghdad over the past decade, that would be a great thing.”

Mohammed believes that the government would not demolish their houses.

“That would anger tens of thousands of people, and that is not something you can confront,” he said.

On December 1, 2022, the Council of Ministers issued a decree regarding changing the type of properties from agricultural to residential in Baghdad, with conditions including that the number of residential units should not be lower than a hundred, they should be provided with public services, and should not conflict with any current or future projects.

The trend of reconstructing agricultural lands and greenery into residential complexes to solve the housing crisis has led to the erosion of the green features of the Iraqi capital, according to civil engineer Farah Ali.

“Many orchards and parks were transformed into private investment and converted to modern residential complexes, leading to a decline in green space proportion to less than 12 percent of Baghdad’s total area,” she said.

According to her, this continuous process that increased with the increasing demand on real estate, and administrative and financial corruption is the main cause of the problem.

“Influential people and those supported by influential parties invest in state-owned lands, and before that they circumvent the law to buy them at low prices,” she said, blaming the fragility of state institutions and absence of accountability that has led to such problems.

Disappearance of Monuments

Baghdad is home to dozens of historical monuments classified as having cultural or national value, but most of them have been neglected and vandalized as a result of bombings carried out by extremist groups from 2003 until mid-2017.

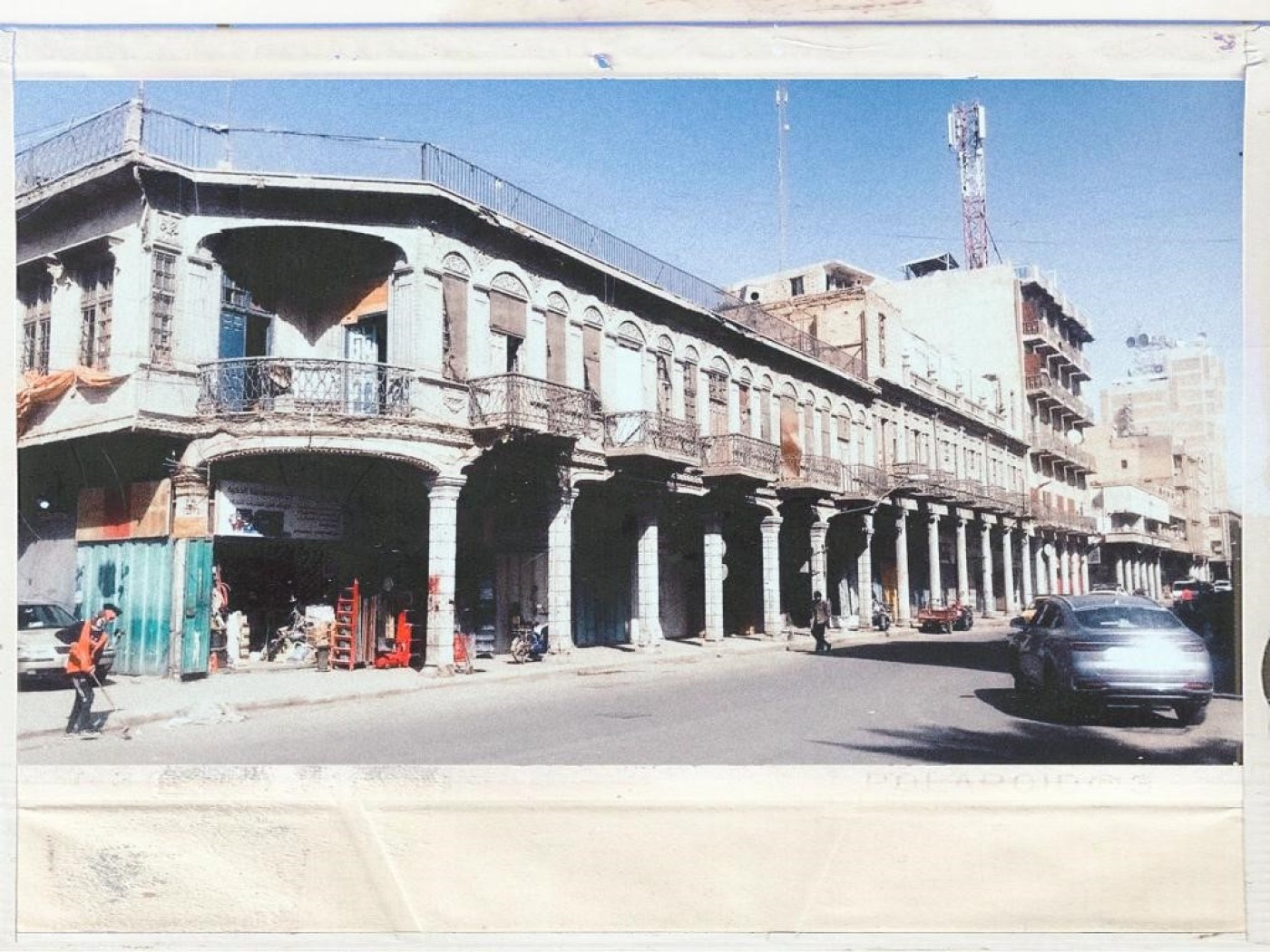

Many of these landmarks are located on al-Rashid street, which is one of the oldest and most famous streets in Baghdad. Its construction dates back to the Ottoman Empire, and it extends from Bab al-Muadham area to Bab al-Sharqi.

There are historical and cultural monuments on both sides of the street, including mosques, schools, and markets, as well as dozens of houses distinguished by their Baghdadi architecture.

However, many of these buildings and landmarks are suffering from neglect or are deliberately destroyed by their owners in order to be able to sell them as a piece of land.

Over the past two decades, most of the street’s landmarks have witnessed governmental neglect and were not maintained or protected from encroachment or extinction, despite the continuous demands of activists and those interested in heritage to revive these landmarks so the street would not lose its identity.

Some accuse the ministry of culture of deliberately neglecting these landmarks, including al-Rashid street. Among them is former minister Mufid al-Jazairi, who held the position in 2005.

“The quota system and political Islam have produced figures who run the ministry of culture, tourism, and antiquities in a way that is not compatible with the requirements for preserving the cultural and heritage identity of Baghdad,” he said.

According to him, many parties reject the position of the minister of culture due to their lack of interest in culture and heritage.

“The problem of lack of interest in heritage is not due to budget or financial allocation, but rather with the interest of those who manage those files,” he said.

Iraqi security authorities have on multiple occasions between 2006 and 2017 reported damages to historical or cultural landmarks in bombings and attacks in Baghdad.

Another form of transgression was carried out by official bodies, an example being the Shia endowment taking over the house of Baha’ullah in Karkh side’s Tala’i neighborhood in 2013, which had been a house of worship for followers of the Baha’i faith.

Its identity was changed and its name became Husseiniyah Sheikh Bashar, despite it being owned by the ministry of culture as a landmark.

Sattar Mohsen is the director of Dar Sutoor publishing and distribution house and is interested in documenting Baghdad’s heritage.

According to him, the destruction of those landmarks is a systematic process with economic factors behind it.

“After the chaos of 2003, the neglect began, the results of which we now see on the landmarks and the parties supporting it,” he said. “It is not in their interest to keep the landmarks standing because of their high financial value.”

“Unfortunately, the responsible authorities see the Baghdadi heritage with spectating eyes and not with a sense of power, hence the major loss that cannot be compensated for,” he said.

Christian Migration

There are currently around 300 to 400 thousand Christians in Baghdad according to Willian Warda, a member of the Hammurabi organization for defending Christian rights, while before 2003, there were over 750,000 Christians in the capital.

Other sources believe that the number of Christians in the country does not exceed 250,000 people, many of whom reside in the Kurdistan Region and are what remain of 1.5 million Christians that lived in the country before 2003.

According to Warda, the migration of Christians from Baghdad has hugely affected its features.

“Most of the Christians in Karrada and 52nd area sold their homes, and they were divided into small houses that resembled human cages, and the Christian neighborhoods in the Doura area were emptied almost entirely of its population of 150,000 Christian,” he said, adding that now their number does not exceed a few thousands.

He indicated that the new non-Christian owners violated the urban style of the houses and completely replaced them after dividing or demolishing them and building other buildings, which harmed the landmarks for which Baghdad was known.

Regarding churches, Warda said that many of them closed their doors because there were no Christians to perform their prayers in them, and the rest of the churches witnessed a significant decline in the number of their patrons.

The churches that used to be filled on special occasions have recently reached a maximum of fifty people entering them on those very same occasions.

Warda is among many who consider themselves the true people of Baghdad and believe that the migration of its people has not only changed the architecture of the city, but the people’s behavior as well.

The scale and nature of the transformations in construction can be seen in the Karrada area, which used to include Christians alongside Shia and Sunni Muslims, where dozens of residential houses built of bricks with large areas in their old style, including gardens and wide corridors, are being demolished, to be replaced by buildings with several floors and facades of plastic and glass.

There were many reasons for the migration of Christians from Baghdad over the past decades.

Some immigrated for political and security reasons following threats they received, and some of them did so because of the migration of their relatives and their remaining alone in the city, or for economic reasons.

Christian journalist Kamal Yaldo, who left Baghdad years ago for political reasons, believes that the latest motive for the increase in the number of Christian immigrants was the fear that ISIS would arrive in Baghdad in 2014, as happened with many Christians in Nineveh Governorate, which the organization took control of on June 10, 2014.

He added that armed militias spread in Baghdad after 2014, imposing taxes and Islamic religious practices on Christians during certain periods, such as requiring women to wear the hijab, which prompted some to leave the city and migrate towards the Kurdistan region, or leave the country.

“After 2003, the militias exercised a siege on Christians under a religious cover, but the motives were purely financial and not religious, which was to seize Christian homes and shops and even churches. In doing so, they took advantage of the weakness of the state and its inability to provide protection for Christians during periods of war and sectarian conflicts,” he said.

Minority rights activist Sargis Youkhana considers the migration of Baghdad’s Christians a reason for the demographic change in some of its neighborhoods, which brought with it a change in its features, recalling what he described as the laxity of the post-2003 governments in the issue of Christian presence.

“All successive governments put the issue of Christians and their migration in their program, but unfortunately, to date, we have not seen serious government action to support the voluntary return of Christian immigrants,” he said.

“The peak of the migration of Baghdad’s Christians occurred between 2004 and 2013 because of their suffering during the era of sectarianism, especially the incident of the Sayyidat al-Najat massacre in 2010, which contributed to bringing about a demographic change in several areas and transforming Christian landmarks into commercial markets, malls, and corporate headquarters, including the Syriac Church in Shorja, which was built in 1834 and now it consists of commercial markets, the Chaldean Monastery in Doura, which is transformed into a commercial building, and others,” Youkhana explained.

According to some people, the solution is for the government to issue laws that seize landmarks from private owners and individuals, putting their fate in safer hands rather than in constant risk of being disposed of.

“The entities that own heritage monuments, such as the Shiite and Sunni endowments, and the Ministry of Culture, have neglected heritage monuments, so they must be pressured by the General Authority for Heritage and Antiquities to do their duty and preserve Baghdad’s landmarks,” researcher and historian Ali al-Nashmi said.

The Director of the Relations and Media Department in the Baghdad Municipality, Muhammad al-Rubaie, confirmed that the years 2023 and 2024 will witness projects to develop the old city of Baghdad in cooperation with the Association of Iraqi Banks, the Central Bank, the Sunni and Shiite Endowment Offices, and other responsible institutions as part of a trend towards reviving Baghdad’s heritage.

"A committee has been formed to draw up a plan for the project, and it has a complete vision for initiating it, and implementation will begin during the current year. Development operations are focused on Al-Rashid Street, with its important Baghdad landmarks and distinctive architecture,” he added.

Kamal Abdullah, a seventy-seven-year-old retired employee, praised the attempts to preserve some of Baghdad’s historic streets and save what remains of its buildings, whether built in the old traditional method known as Shanashil or otherwise, as they embody the cultural face of Baghdad.

“Houses with beautiful, peaceful views and gardens planted with flowers and trees are destined to be demolished and transformed into concrete blocks with facades of painted brick or glass and plastic,” he said in disappointment.

“The issue is not related to the need imposed by the huge increase in population, but rather to culture, public taste, and reaping profits,” he added.

*This feature was produced in collaboration with the Network of Iraqi Reporters for Investigative Journalism (NIRIJ)

Facebook

Facebook

LinkedIn

LinkedIn

Telegram

Telegram

X

X